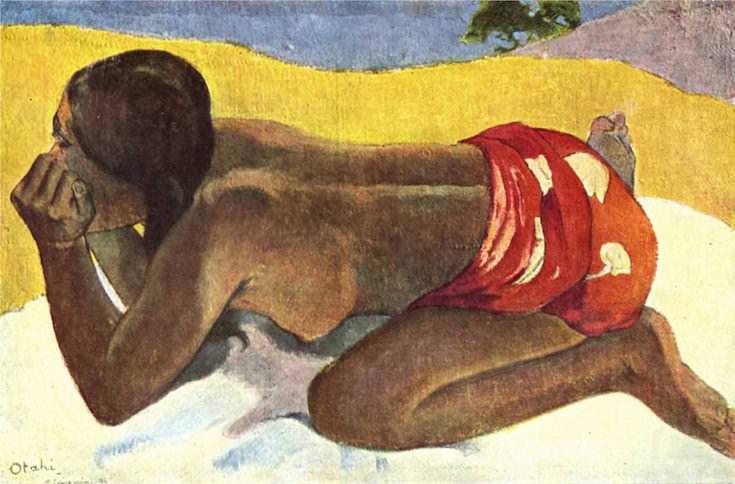

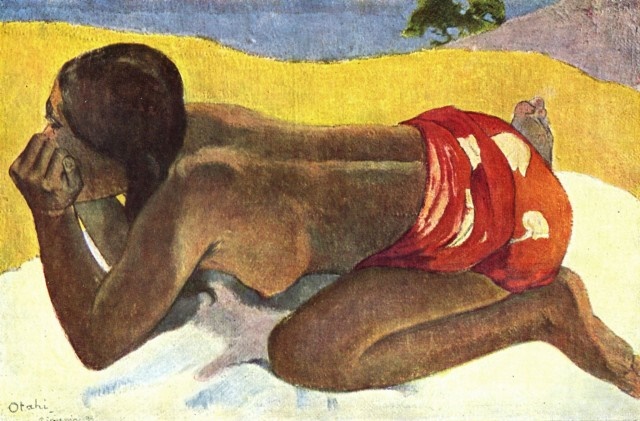

Paul Gauguin, "Alone"

"Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object -- and most particularly an object of vision: a sight."-John Berger, "Ways of Seeing"

"Ways of Seeing" was published in 1970. Penned by John Berger, it remains a seminal work of art criticism. Substantial discussion is devoted to the role of the observer in European oil painting from the 14th century to early 19th century. If you have been to a museum of art, you too have assumed this role.

A walk through a popular museum of art or a search on the internet makes it abundantly clear that the portrayal of women is a popular subject in painting. More often than not they are unclothed. This image of a nude woman in painting invites spectatorship. Berger argues that the history of women in art is not as a participant but as an object.

Five years later Laura Mulvey would publish "Visual Pleasure and Narrative cinema," a seminal work of feminist art theory. Mulvey and Berger argue similarly as regards the female nude, the former focusing her research on the modern art of cinema rather than the traditional art of oil painting. It did not escape Mulvey that though moving pictures were a modern art form they illustrated the same psychological preoccupations as traditional art forms. Mulvey's paper introduces the term "male gaze". As the time of the Old Masters passed the Industrial Revolution ushered in the age of Modern Art, a prime time for the male gaze.

Manet, "Luncheon On The Grass"

In the world of curating and exhibitions, paintings executed in the 1860s and forward are designated under the Modern Art moniker. Edouart Manet's "Luncheon on the Grass" of 1862 is commonly regarded as an important first mile marker. This designation is a bit ambitious and lacks discrete classification. Modern Art at this early period does not illustrate quite the quantum leap from past towards future as Cubism would a few decades later. At the time of Manet Modern Art's reference point was still very much warm in the grave.

Berger argued that this nomenclature, which indicates a break in tradition, is semantic. Manet was a painter who carried on the tradition of painting nudes. The woman is in a classic odalisque pose, and yet accompanied by two fully dressed men. The women in Manet's painting move from a "sight" to a "sight for the dressed." I detect a further undertone. Manet portrays a woman who is part of a transaction between artist and dealer, the two men. She bears direct witness to that transaction but she has no input into the outcome of that transaction.

I recall sitting in on an art history lecture on the Greek Classical period. The image being discussed was of a woman carved in relief discovered at the Temple of Athena Nike. In the relief, the woman is fixing her sandal. The professor explained the carnality of the sandal at great length. I was intrigued that I had not heard any such enthusiasm of description offered to any of the countless male works that had been viewed throughout the course. Perhaps that is because the male figures always had heads. The image of the woman in question had no head. To this day it has not been discovered. Where there is a head, there is the ascribing of personality and humanity. This woman had been dehumanized. She is robbed of her capacity to avert the male gaze.

For Mulvey this would be an extreme application of her theory. It is nonetheless, neatly encapsulating.

The opportunity afforded to painting and art in general beginning at the time of Manet was that it no longer had to be tethered to the act of representing the human form. The headless woman at the temple of Nike Athena could be bequeathed a rich inner life by new creators. Yet the banner of representation and the baggage of its psychology could not be discarded so easily. From 1860 to about 1950 Modern Art would carry on the tradition of an interminable and clear male gaze punctuated by a break for lunch (see: Cubism). I discuss here a sampling of highly regarded Modern Art paintings.

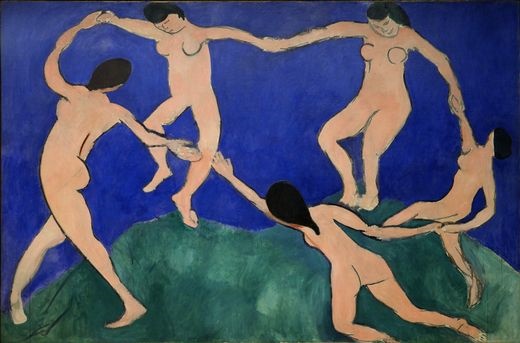

Matisse, "The Dance," 1909

Matisse would return frequently to the odalisque as subject matter. "The Dance" can be seen as a composite study of different odalisques in a group. It can also be viewed as a representation of the same model from various perspectives. The anonymous women or woman float weightlessly on the backdrop of a cloudless sky on the brink of an endless cliff. Their dance is reckless and they risk everything. "The Dance" here, is that of carnal pleasure. As the woman in the right foreground shows this cycle risks being broken. That the cycle may be broken is strictly a female concern. There are no men there to partake of the repercussions incurred. It is true that not all of the women Matisse painted were nudes or were anonymous. 1910's "Music" depicts two fully clothed women. Beyond two pupil-less slits and comically drawn breasts one figure strokes a guitar sans headstock. This accentuated phallus is Matisse's but it is also that of the viewer's.

Paul Gauguin, "The Spirit of the Dead Keep Watch," 1892 and "Alone" (pictured), 1893

In the early 1890s Paul Gauguin tired of French life and went to Tahiti in search of adventure and new subjects. During this decade long trip which ended with his death in 1903 Gauguin's art would be exclusively of portraits of native women. The subject in "The Spirit of the Dead Keep Watch" has an inverted odalisque pose. She lies submissive, accompanied only by the watchful eye of an intruder. This intruder is presumed to be that of her betrothed or a mythical figure representing death. Similar to Matisse's "The Dance" this painting hits upon a major binary role of women of late 19th century modernist art, the role of the woman as sexually available fertility goddess and the role of woman as a harlot, a harbinger of death. In "Alone" Gauguin eliminates scenery. This woman is crouched in an animal position waiting to be mounted. In a seeming gloat by 1902's "Barbarian Stories" he struggles to stay objective. He interjects himself visibly into the frame as a taloned, impish figure. The two female subjects appear unaware of his presence.

Gustav Klimt "The Kiss", 1907, "Hope I," 1903, "Three Ages of Woman," 1905 (pictured)

Gustav Klimt's most well-known image is "The Kiss." It is a rare work in that the artist rarely painted men. While it appears to delineate passion there is equally aggressive intent. The man's head is higher than the woman's. He grips her head definitively, positioning it in a way that causes her to limp from her own feeling of passion, but also as a recoil from his threat. She does not look at him.

In other works Klimt provides a broader exploration of female emotion and choice. He was deeply influenced by religious art and often presented his women as icons. It is with a startlingly lifelike gaze that Klimt's women appear to judge more definitively than the viewer. In a slight twist on the binary theme of woman as representing the possibility of fornication or the nearness of death Klimt painted "Hope I" and "Mother Child". Fornication here has the consequence of child birth, the mother shielding her child away from looming death.

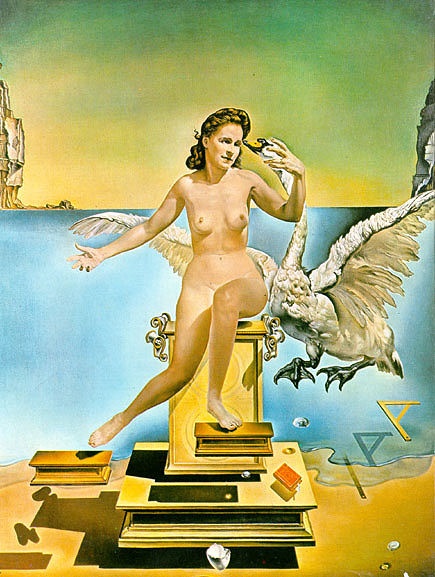

Salvador Dali, "Bleeding Roses," 1930, "Leda Atomica," 1949 (pictured), "Galarina," 1941

The bulk of Surrealism was preoccupied with purgatory. Neither men nor women could escape this waiting room leading to death. The Surrealists made good on providing a venue for artists to paint headless female torsos and full bodied women in inexplicable but hopeless situations. Salvador Dalí would serve as the unlikely departure from these renderings. In his oeuvre, "Bleeding Roses" from 1930 stands out. In his early work Dalí rarely painted women. This woman is clearly in pain. In all his work thereafter involving women Dalí would focus on painting his wife Gala. That Dali worshipped his wife was clear. In "Leda Atomica"she sits on a pedestal embracing a swan. It is a rare example of a woman engaging in a non-sexual action with a tool of symbolism at her disposal. In 1944's "Galarina" she is a maternal figure clothed and offering the viewer one breast.

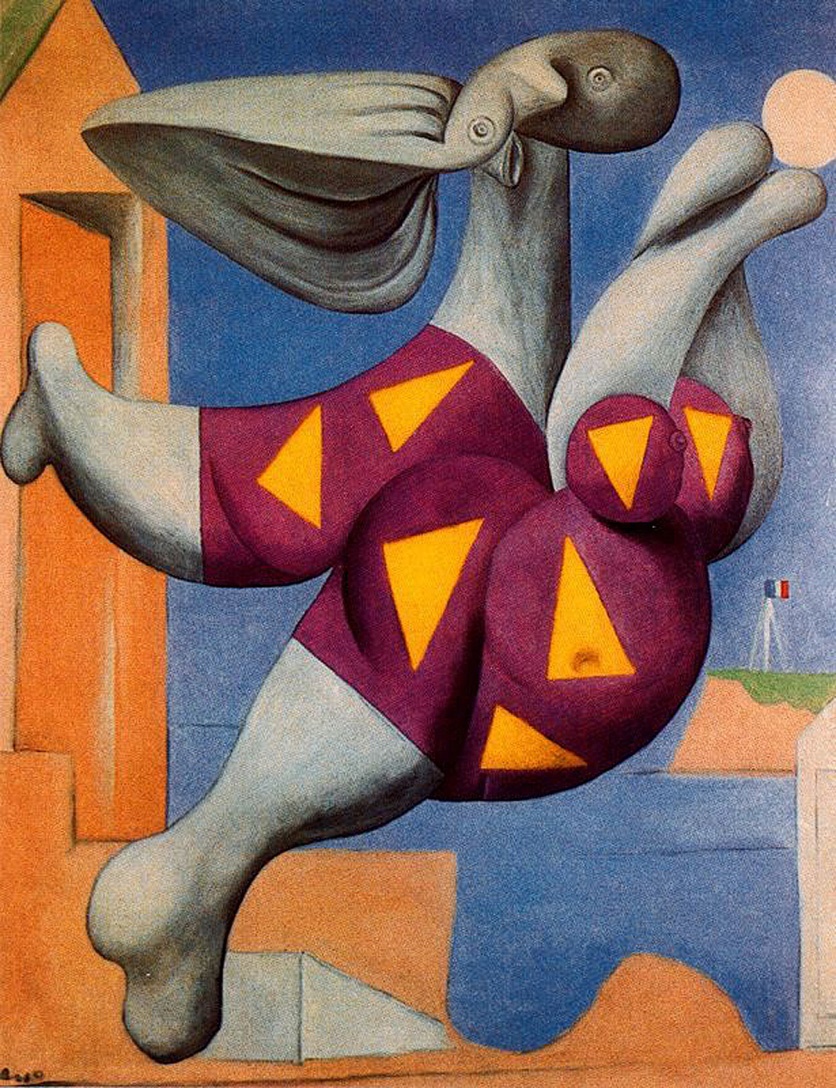

Picasso, "Demoiselles de Avignon," 1907 and "Bather with Beach Ball," 1932 (pictured)

Picasso was a legendary womanizer. Out of all the modernist painters it is difficult to ignore his well documented affairs. These subjects would often appear in his painting as women idolized, despised, or neglected. 1907's "Demoiselles de Avignon" is the artist's take on the traditional brothel scene. More importantly it would function as a step which would prepare critics and audiences for Cubism. The prostitutes in "Demoiselles de Avignon" are impossibly angular, rendered in an insouciant and nearly comical way. The masked ones appeal to the primitive senses. The unmasked extend a more subtle invitation to the higher society art viewer. At its time it was shocking, viewed as a deliberately unglamorous portrait of female sexuality, a mess of geometric pornography. Such a man drawing such a scene could not have any high regard for the purveyors of carnality. Eventually Picasso would outdo himself with 1932's "Bather with Beach Ball," a painting of his young mistress, in which she is depicted as blow up beach ball.

As a purveyor of male gaze, Picasso was unparalleled. He would have agreed with John Berger's pithy statement on the nude's place in painting "Those who are not judged beautiful are not beautiful. Those who are, are beautiful. They are given the prize. The prize is to be owned. That is to be available."

![By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/profile/public/images/article/2019-06/Bell.png?itok=gWp6s_Y0)